SUMO Tag: A tool to improve recombinant protein solubility and expression level in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic host

|

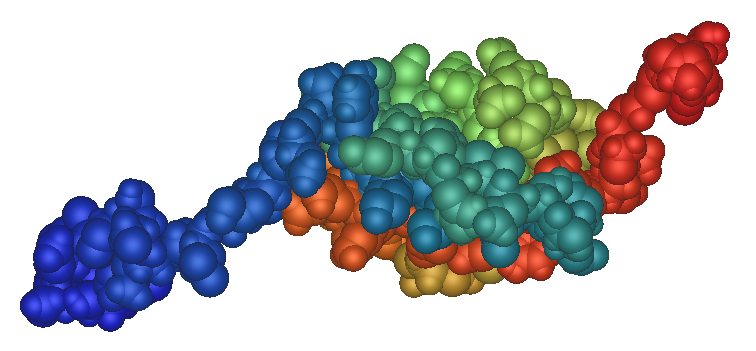

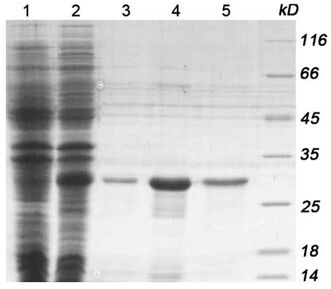

SUMO Research: from Function Study to Recombinant Protein Tag Small Ubiquitin-like Modifiers (SUMOs) are a group of small proteins that can be conjugated to an expressing protein through enzymatic reaction, during the post-translation process. The whole procedure can be named as “SUMOylation”. SUMO-1 was the first to be identified in the SUMO family back in 1996[1], but the name “SUMO” came out one year later in 1997[2]. SUMO-1 is a highly conserved, small ubiquitin-related modifier that has been shown to be covalently conjugated to a large variety of cellular proteins; these SUMOylated proteins show higher stability [1, 2]. Like ubiquitin, the SUMO can be attached and detached from the protein through in vivo enzymatic reaction; and the most important feature is the SUMO cleavage that goes through structure recognition with no residue remaining on the protein [3]. Study demonstrated that ubiquitin can serve as a reconstructed protein tag which increases the expression level in e.coli [4] and in yeast [5]. After the discovery and function study of SUMOs, the role as a recombinant protein tag enhancing the solubility and expression level in e.coli was introduced together with the SUMO cleavage method [6]. However, the wild type SUMO can only be used for prokaryotic expression hosts like e.coli, while expressing tagged proteins. In eukaryotic hosts, the expression enhancing function of wild type SUMO is still observed and a so called “split SUMO” solution can be applied [7]. A mutated SUMO sequence (from Yeast SUMO) was later on developed to adapt to eukaryotic expression host, which is capable to maintain high protein expression level and avoid fusion protein being un-tagged. This feature has been proven in both insect and mammalian expression systems [8, 9]. The SUMO tags are a group of small protein either directly from or mutated from wild type yeast SUMO (smt3). They serve as recombinant protein companion and function as solubility enhancer and expression booster. Depending on the different sequences, the SUMO tags can be used for either prokaryotic or eukaryotic hosts such as e.coli, yeast (Saccharomyces, Pichia), insect cell/baculovirus systems and mammalian cell (CHO, HEK293). The SUMO tag will be firstly incorporated with an affinity tag then expressed together with the target protein by the host, followed by enzyme activity to detach the SUMO tag. During purification process, the SUMO tag will be immobilized by the affinity tag and be separated from the target protein. |

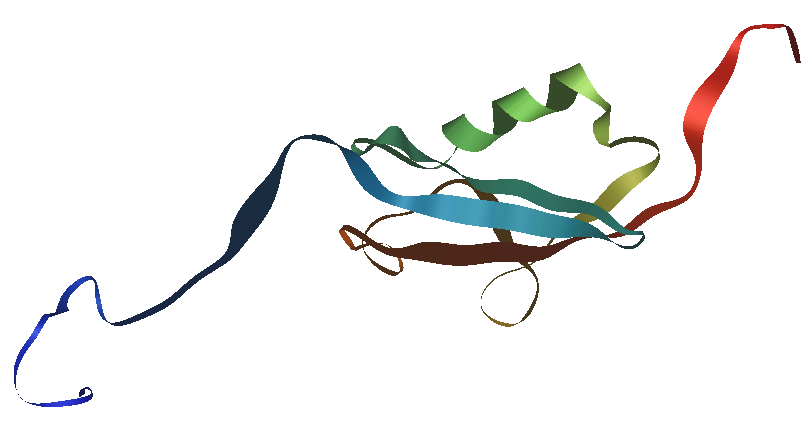

Fig.1 Human SUMO1 structure.

Structure schematic of human SUMO1 protein made with iMol and based on PDB file 1A5R, an NMR structure; the backbone of the protein is represented as a ribbon, highlighting secondary structure; N-terminus in blue, C-terminus in red. The image under is the same structure representing atoms as spheres. |

Applications (key words are shown in the list)

We have gathered several case studies to demonstrate the function of SUMO tag in recombinant protein expression. Different types of applications are simplified into key words, listed hereunder in the table. Each case study corresponding to multiple key words, as well as each individual key word may correspond to multiple case studies. Under the title of each case study , the corresponding key words are shown.

E.coli |

B.subtilis |

Saccharomyces |

Pichia |

Baculovirus |

Insect cell |

CHO |

HEK293 |

Mammalian cell expression |

bioactivity |

Enzyme and enzyme activity |

Toxic protein |

Hard-to-express protein |

Protein folding |

Large size protein |

Membrane protein |

Soluble expression |

1. Heparin-Binding Epidermal Growth Factor (HB-EGF) expression and bioactivity recovery

Key words: hard-to-express protein; e.coli; bioactivity; HB-EGF; soluble expression

Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF) can stimulate the division of various cell types and has potential clinical applications that stimulate growth and differentiation. The high expression of active HB-EGF in Escherichia coli has not been successful as the protein contains three intra-molecular disulfide bonds, which makes it difficult to form correctly in the bacterial intracellular environment.

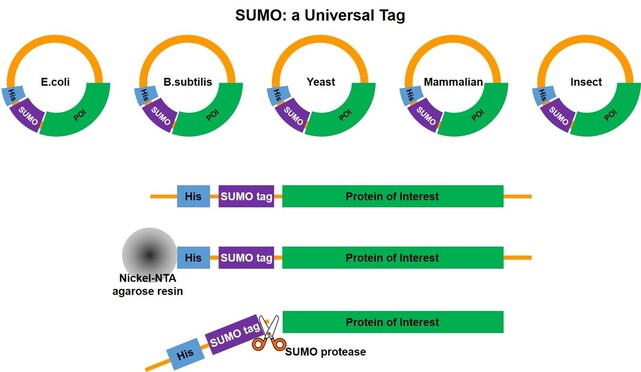

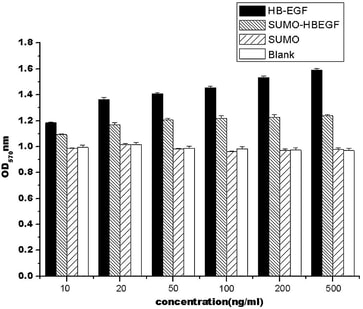

N-terminal His-SUMO tag was used for recombinant HB-EGF expression. The soluble expression level was tested at 104mg/L e.coli culture (the actual volume is 500mL). After SUMO tag removal, the bioactivity of HB-EGF recovered successfully and show dose dependent bioactivity in MTT assay.

Key words: hard-to-express protein; e.coli; bioactivity; HB-EGF; soluble expression

Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF) can stimulate the division of various cell types and has potential clinical applications that stimulate growth and differentiation. The high expression of active HB-EGF in Escherichia coli has not been successful as the protein contains three intra-molecular disulfide bonds, which makes it difficult to form correctly in the bacterial intracellular environment.

N-terminal His-SUMO tag was used for recombinant HB-EGF expression. The soluble expression level was tested at 104mg/L e.coli culture (the actual volume is 500mL). After SUMO tag removal, the bioactivity of HB-EGF recovered successfully and show dose dependent bioactivity in MTT assay.

|

Fig 1-1. Expression and purification of SUMO-HBEGF in BL21 (DE3). 1: total cellular extracts from E. coli BL21 (DE3) containing pET28a/SUMO-HBEGF without IPTG introduction; 2: total cellular extracts from E. coli BL21 (DE3) containing pET28a/SUMO-HBEGF introduced with 0.4 mM IPTG in 20︒C; 3–5: purified recombinant His6-tagged SUMO-HBEGF with nickel-affinity chromatography.

|

Fig 1-2. Mitogenic activity analysis of different concentrations HB-EGF and SUMO-HBEGF to the NH-3T3 cells in vitro. Data are presented as means standard deviation from three independent experiments in which all of the samples were tested in triplicate.

|

2. Toxic Lacticin Q expression in E.coli and bioactivity test

Key words: Toxic protein; E.coli; bioactivity; Lacticin Q

Lacticin Q is a broad-spectrum class II bacteriocin with potential as an alternative to conventional antibiotics. Only low levels of Lacticin Q can be obtained through growth of the natural producer strains, and the compound is difficult to purify. Heterologous expression is a good alternative method, however the broad antibacterial spectrum and high susceptibility to proteolytic degradation of bacteriocins pose difficulties for their direct expression in E. coli.

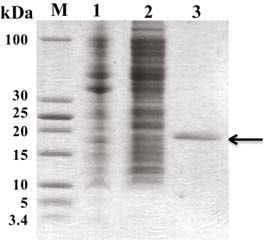

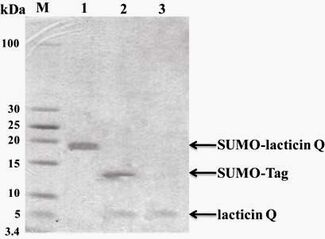

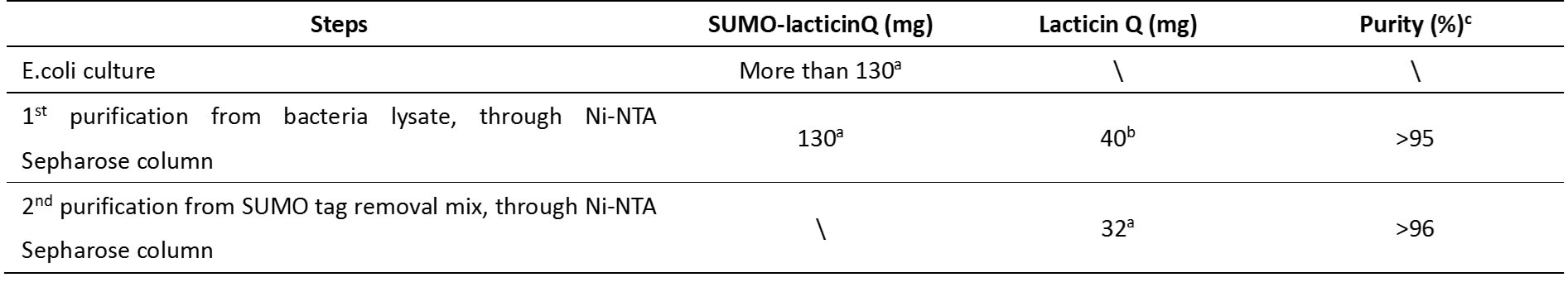

N-terminal His-SUMO tag was used to express the lacticin Q in e.coli culture. 130mg His-SUMO-LacticinQ was purified from soluble fraction of bacteria lysate and the purity is above 95%. According to molecular weight calculation, 40mg of which was Lacticin Q. The fusion protein was then operated to remove the His-SUMO tag and purified again. 32mg Lacticin Q was obtained and the purity is above 96%.

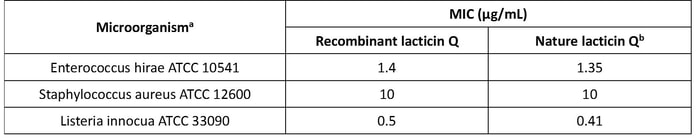

The bioactivity was tested and compared with nature Lacticin Q. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by a liquid growth inhibition assay using Enterococcus hirae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Listeria innocua as indicator strains. The indicator organisms were cultured at 37°C until the optical density reached the logarithmic stage, and distributed into a 96-well plate with 105 cells per well (90 μL). The cells were then treated with 10 μL of purified lacticin Q at a series of concentrations. Each assay was repeated three times. Result show that the recombinant and nature Lacticin Q have equal bioactivity.

Key words: Toxic protein; E.coli; bioactivity; Lacticin Q

Lacticin Q is a broad-spectrum class II bacteriocin with potential as an alternative to conventional antibiotics. Only low levels of Lacticin Q can be obtained through growth of the natural producer strains, and the compound is difficult to purify. Heterologous expression is a good alternative method, however the broad antibacterial spectrum and high susceptibility to proteolytic degradation of bacteriocins pose difficulties for their direct expression in E. coli.

N-terminal His-SUMO tag was used to express the lacticin Q in e.coli culture. 130mg His-SUMO-LacticinQ was purified from soluble fraction of bacteria lysate and the purity is above 95%. According to molecular weight calculation, 40mg of which was Lacticin Q. The fusion protein was then operated to remove the His-SUMO tag and purified again. 32mg Lacticin Q was obtained and the purity is above 96%.

The bioactivity was tested and compared with nature Lacticin Q. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by a liquid growth inhibition assay using Enterococcus hirae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Listeria innocua as indicator strains. The indicator organisms were cultured at 37°C until the optical density reached the logarithmic stage, and distributed into a 96-well plate with 105 cells per well (90 μL). The cells were then treated with 10 μL of purified lacticin Q at a series of concentrations. Each assay was repeated three times. Result show that the recombinant and nature Lacticin Q have equal bioactivity.

|

Fig.2-1 Tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis for the purification of His-SUMO-lacticinQ fusion protein. The eluted fusion protein showed 95% or higher purity by electrophoretic analysis with Tricine-SDS-PAGE(analyzed by Bandscan software, BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.). Lanes: M, protein markers; 1, precipitate of bacteria lysate (insoluble fraction); 2, supernatant of bacteria lysate (soluble fraction); 3, elution fractions from soluble expressed. Arrow indicates the purified fusion protein.

|

Fig.2-2 Tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis of SUMO-lacticin Q fusion protein cleaved by SUMO protease and recombinant lacticin Q purification. Lanes: M, protein markers; 1, purified His-SUMO-lacticinQ fusion protein; 2, mixture of His-SUMO and lacticin Q after SUMO protease cleavage; 3, purified recombinant lacticin Q by Ni-NTA.

|

Table 2-1. Isolation of recombinant lacticin Q from SUMO-lacticin Q fusion protein

a - Based on 1 L of bacterial culture (about 60 g wet weight). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford protein assay.

b - The amount of recombinant lacticin Q was calculated based on molecular weight.

c - Purity of protein or peptide was estimated by SDS gel stained by Coomassie blue.

a - Based on 1 L of bacterial culture (about 60 g wet weight). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford protein assay.

b - The amount of recombinant lacticin Q was calculated based on molecular weight.

c - Purity of protein or peptide was estimated by SDS gel stained by Coomassie blue.

Table 2-2. The MIC of recombinant lacticin Q and native lacticin Q to selected microorganisms

a - Abbreviations: ATCC, American Type Culture Collection

b - The MIC value of native lacticin Q is from the original data of Fujita et al. (2007)

a - Abbreviations: ATCC, American Type Culture Collection

b - The MIC value of native lacticin Q is from the original data of Fujita et al. (2007)

3. Tryptase protein expressed in baculovirus insect cell expression system

Key words: baculovirus, insect cell, human tryptase

Tryptase is a trypsin-like protease with a unique tetrameric structure. It is stored as an active enzyme in mast cell secretory granules and has been implicated in the etiology of asthma and other allergic and inflammatory disorders. Both human tryptase -α and -β form a ring-like tetramer with active sites facing an oval central pore. The tetrameric structure of tryptase-α is stabilized by sulfated polysaccharides, e.g. heparin. In the absence of such polymeric anions, tryptase-α reversibly converts to an inactive conformation and dissociates into monomers. Tryptase-β is more stable although it also requires a polymeric anion for maximal activity. Sf9 cell line was used to express the different fusion proteins. GP67 (G as shown in the result) signaling peptide was used as leader sequence for secreted expression.

Key words: baculovirus, insect cell, human tryptase

Tryptase is a trypsin-like protease with a unique tetrameric structure. It is stored as an active enzyme in mast cell secretory granules and has been implicated in the etiology of asthma and other allergic and inflammatory disorders. Both human tryptase -α and -β form a ring-like tetramer with active sites facing an oval central pore. The tetrameric structure of tryptase-α is stabilized by sulfated polysaccharides, e.g. heparin. In the absence of such polymeric anions, tryptase-α reversibly converts to an inactive conformation and dissociates into monomers. Tryptase-β is more stable although it also requires a polymeric anion for maximal activity. Sf9 cell line was used to express the different fusion proteins. GP67 (G as shown in the result) signaling peptide was used as leader sequence for secreted expression.

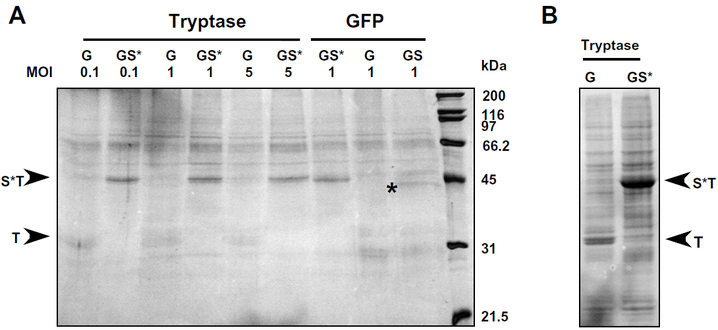

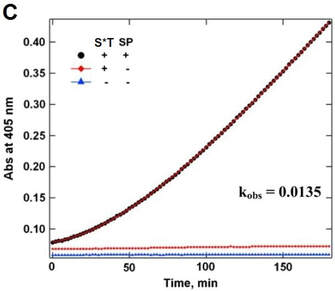

Fig.3-1 Analysis of the secretion of Tryptase bII and GFP into the medium by Sf9 cells.

G: reconstructed plasmid containing gp67–tryptase; GS: reconstructed plasmid gp67SUMO–tryptase; GS*: reconstructed plasmid gp67SUMOstar–tryptase; T: protein tryptase; ST: protein SUMOstar–tryptase (Not shown on the image. The same MW as S*T); S*T: protein SUMOstar–tryptase.

(A) Cells (10^4) were infected with baculovirus harboring either gp67–tryptase (G), gp67SUMO–tryptase (GS) or gp67SUMOstar–tryptase (GS*) at MOIs of 0.1, 1 or 5 in 6 well plates. The corresponding fusions to GFP were only analyzed at an MOI of 1. Conditioned medium from each well was collected at 72 h post-infection and clarified by centrifugation at 300g for 10 min. The clarified samples were concentrated using a 0.5 ml Microcon concentrator (MWCO 10 kDa, Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 14,000g for 40 min. Equal amounts of the concentrated media were loaded in each lane.

(B) Aliquots of the cells expressing either G–tryptase or GS*–tryptase were lysed and analyzed by SDS–PAGE in order to determine if the fusion proteins were being retained within the cells. Following electrophoresis, the separated proteins were stained with Coomassie blue.

(C) Bioactivity test before and after SUMOstar tag removal. Protein was purified from Sf9 culture medium. The pooled and concentrated eluate fraction was assayed for tryptase activity with and without removal of the SUMOstar fusion partner by incubation with SUMOstar protease using Chromozym TH as a substrate for tryptase. (●) Complete reaction mixture with SUMOstar protease, heparin, and SUMOstar–tryptase. (◆) Reaction mixture with heparin and SUMOstar–tryptase but without SUMOstar protease. (▲) Reaction mixture minus SUMOstar–tryptase and SUMOstar protease. In a separate experiment SUMOstar protease was found to have no activity against the tryptase substrate (data not shown).

G: reconstructed plasmid containing gp67–tryptase; GS: reconstructed plasmid gp67SUMO–tryptase; GS*: reconstructed plasmid gp67SUMOstar–tryptase; T: protein tryptase; ST: protein SUMOstar–tryptase (Not shown on the image. The same MW as S*T); S*T: protein SUMOstar–tryptase.

(A) Cells (10^4) were infected with baculovirus harboring either gp67–tryptase (G), gp67SUMO–tryptase (GS) or gp67SUMOstar–tryptase (GS*) at MOIs of 0.1, 1 or 5 in 6 well plates. The corresponding fusions to GFP were only analyzed at an MOI of 1. Conditioned medium from each well was collected at 72 h post-infection and clarified by centrifugation at 300g for 10 min. The clarified samples were concentrated using a 0.5 ml Microcon concentrator (MWCO 10 kDa, Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 14,000g for 40 min. Equal amounts of the concentrated media were loaded in each lane.

(B) Aliquots of the cells expressing either G–tryptase or GS*–tryptase were lysed and analyzed by SDS–PAGE in order to determine if the fusion proteins were being retained within the cells. Following electrophoresis, the separated proteins were stained with Coomassie blue.

(C) Bioactivity test before and after SUMOstar tag removal. Protein was purified from Sf9 culture medium. The pooled and concentrated eluate fraction was assayed for tryptase activity with and without removal of the SUMOstar fusion partner by incubation with SUMOstar protease using Chromozym TH as a substrate for tryptase. (●) Complete reaction mixture with SUMOstar protease, heparin, and SUMOstar–tryptase. (◆) Reaction mixture with heparin and SUMOstar–tryptase but without SUMOstar protease. (▲) Reaction mixture minus SUMOstar–tryptase and SUMOstar protease. In a separate experiment SUMOstar protease was found to have no activity against the tryptase substrate (data not shown).

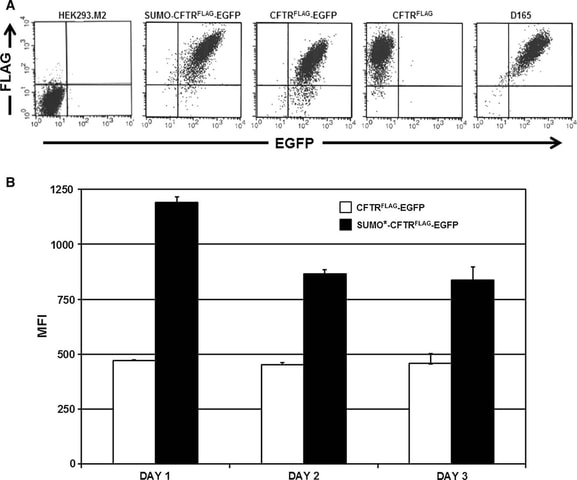

4. CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) expressed by HEK293

Key words: transmembrane protein, HEK293, Mammalian expression, Large size protein, membrane protein, bioactivity, CRTR

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that encodes a chloride channel belonging to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. The most frequent genetic mutation associated with clinical CF disease is deletion of phenylalanine at position 508 (ΔF508) in CFTR. The DF508 mutation results in aberrant folding of the CFTR protein, retention of CFTR in the endoplasmic reticulum, and premature CFTR protein degradation. Interestingly, wild-type CFTR (wtCFTR) appears to fold, mature, and reach the plasma membrane less efficiently compared to other ABC transporters.

In this study, CFTR was modified with various tags, including a His10 purification tag, the SUMOstar (SUMO*) domain, an extracellular FLAG epitope, and an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), each alone or in various combinations. Expressed in HEK293 cells, recombinant CFTR proteins underwent complex glycosylation, compartmentalized with the plasma membrane, and exhibited regulated chloride-channel activity with only modest alterations in channel conductance and gating kinetics.

Result: Surface CFTR expression level was enhanced by the presence of SUMO* on the N-terminus. Quantitative massspectrometric analysis indicated approximately 10 % of the total recombinant CFTR (SUMO*–CFTRFLAG–EGFP) localized to the plasma membrane. Trial purification using dodecylmaltoside for membrane protein extraction reproducibly recovered 178 ± 56 ug SUMO*–CFTRFLAG–EGFP per 10^9 cells at 80 % purity.

Key words: transmembrane protein, HEK293, Mammalian expression, Large size protein, membrane protein, bioactivity, CRTR

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that encodes a chloride channel belonging to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. The most frequent genetic mutation associated with clinical CF disease is deletion of phenylalanine at position 508 (ΔF508) in CFTR. The DF508 mutation results in aberrant folding of the CFTR protein, retention of CFTR in the endoplasmic reticulum, and premature CFTR protein degradation. Interestingly, wild-type CFTR (wtCFTR) appears to fold, mature, and reach the plasma membrane less efficiently compared to other ABC transporters.

In this study, CFTR was modified with various tags, including a His10 purification tag, the SUMOstar (SUMO*) domain, an extracellular FLAG epitope, and an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), each alone or in various combinations. Expressed in HEK293 cells, recombinant CFTR proteins underwent complex glycosylation, compartmentalized with the plasma membrane, and exhibited regulated chloride-channel activity with only modest alterations in channel conductance and gating kinetics.

Result: Surface CFTR expression level was enhanced by the presence of SUMO* on the N-terminus. Quantitative massspectrometric analysis indicated approximately 10 % of the total recombinant CFTR (SUMO*–CFTRFLAG–EGFP) localized to the plasma membrane. Trial purification using dodecylmaltoside for membrane protein extraction reproducibly recovered 178 ± 56 ug SUMO*–CFTRFLAG–EGFP per 10^9 cells at 80 % purity.

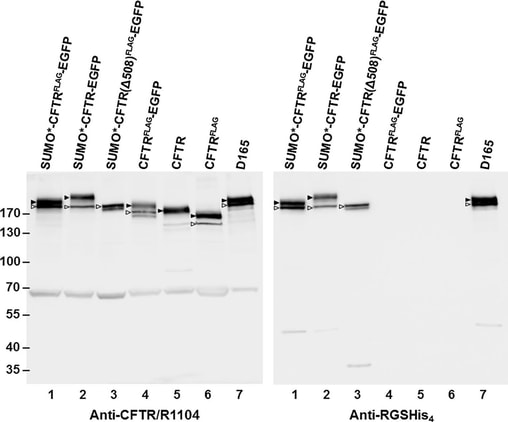

Fig.4-1 Western blot analysis of recombinant CFTR expression.

Puromycin resistant and dox-induced monolayer cultures of transduced HEK293.M2 cells were lysed in Laemmli sample buffer, adjusted to 5×10^4 cell equivalents per 10uL, and analyzed by immunoblotting with either anti-CFTR mAb R1104 or anti-RGSHis4 mAb. Arrowheads mark complex-glycosylated (band C) and coreglycosylated (band B) forms of CFTR. In FLAG-tagged proteins, one of the two sites for N-glycosylation was disrupted. By densitometry, about 68 % and 33 ± 10 % (n = 10) of the SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP protein was found in bands C and B, respectively. Molecular weight markers are shown on the left in kDa. Calculated masses of the SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, and CFTR polypeptides are 212, 197, and 168 kDa, respectively. The 65 kDa band recognized by CFTR-specific antibody R1104 was not observed with RGS-His antibody or by in-gel EGFP fluorescence and could represent a CFTR fragment or nonspecific cross-reactive protein. The results shown are representative of two independent analyses.

Puromycin resistant and dox-induced monolayer cultures of transduced HEK293.M2 cells were lysed in Laemmli sample buffer, adjusted to 5×10^4 cell equivalents per 10uL, and analyzed by immunoblotting with either anti-CFTR mAb R1104 or anti-RGSHis4 mAb. Arrowheads mark complex-glycosylated (band C) and coreglycosylated (band B) forms of CFTR. In FLAG-tagged proteins, one of the two sites for N-glycosylation was disrupted. By densitometry, about 68 % and 33 ± 10 % (n = 10) of the SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP protein was found in bands C and B, respectively. Molecular weight markers are shown on the left in kDa. Calculated masses of the SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, and CFTR polypeptides are 212, 197, and 168 kDa, respectively. The 65 kDa band recognized by CFTR-specific antibody R1104 was not observed with RGS-His antibody or by in-gel EGFP fluorescence and could represent a CFTR fragment or nonspecific cross-reactive protein. The results shown are representative of two independent analyses.

Fig. 4-2 Analysis of recombinant CFTR expression by flow cytometry.

A Cells were treated with 1 ug/mL of dox for 24 h and then livestained for surface FLAG/CFTR expression using SureLight anti-FLAG mAb. The distribution of fluorescence intensity of EGFP and FLAG staining is shown for each of the cell populations analyzed: HEK293.M2 (control), SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, CFTR(FLAG), and D165. D165 is a clonal derivative of the D158 cell line expressing SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP. HEK293.M2 cells that do not express CFTR were included as a negative control.

B The indicated cultures were immunostained for cell-surface FLAG epitope 24, 48, or 72 h after dox induction and analyzed by flow cytometry as in (a). LinearFlow Fluorescently labeled polystyrene beads (Molecular Probes) were analyzed in parallel to control for possible inter-assay variation of the flow cytometer. MFI values for each cell population were calculated from two independent experiments.

A Cells were treated with 1 ug/mL of dox for 24 h and then livestained for surface FLAG/CFTR expression using SureLight anti-FLAG mAb. The distribution of fluorescence intensity of EGFP and FLAG staining is shown for each of the cell populations analyzed: HEK293.M2 (control), SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP, CFTR(FLAG), and D165. D165 is a clonal derivative of the D158 cell line expressing SUMO*–CFTR(FLAG)–EGFP. HEK293.M2 cells that do not express CFTR were included as a negative control.

B The indicated cultures were immunostained for cell-surface FLAG epitope 24, 48, or 72 h after dox induction and analyzed by flow cytometry as in (a). LinearFlow Fluorescently labeled polystyrene beads (Molecular Probes) were analyzed in parallel to control for possible inter-assay variation of the flow cytometer. MFI values for each cell population were calculated from two independent experiments.

References

[1] Matunis MJ, Coutavas E, Blobel G. A novel ubiquitin-like modification modulates the partitioning of the Ran-GTPase-activating protein RanGAP1 between the cytosol and the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1996 Dec;135(6 Pt 1):1457-70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1457. PMID: 8978815; PMCID: PMC2133973.

[2] Mahajan R, Delphin C, Guan T, Gerace L, Melchior F. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell. 1997 Jan 10;88(1):97-107. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81862-0. PMID: 9019411.

[3] Kim KI, Baek SH, Chung CH. Versatile protein tag, SUMO: its enzymology and biological function. J Cell Physiol. 2002 Jun;191(3):257-68. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10100. PMID: 12012321.

[4] Butt TR, Jonnalagadda S, Monia BP, Sternberg EJ, Marsh JA, Stadel JM, Ecker DJ, Crooke ST. Ubiquitin fusion augments the yield of cloned gene products in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Apr;86(8):2540-4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2540. PMID: 2539593; PMCID: PMC286952.

[5] Ecker DJ, Stadel JM, Butt TR, Marsh JA, Monia BP, Powers DA, Gorman JA, Clark PE, Warren F, Shatzman A, et al. Increasing gene expression in yeast by fusion to ubiquitin. J Biol Chem. 1989 May 5;264(13):7715-9. PMID: 2540202.

[6] Malakhov MP, Mattern MR, Malakhova OA, Drinker M, Weeks SD, Butt TR. SUMO fusions and SUMO-specific protease for efficient expression and purification of proteins. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2004;5(1-2):75-86. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029237.70316.52. PMID: 15263846.

[7] Butt TR, Edavettal SC, Hall JP, Mattern MR. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2005 Sep;43(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016. Epub 2005 Apr 9. PMID: 16084395; PMCID: PMC7129290.

[8] Peroutka RJ, Elshourbagy N, Piech T, Butt TR. Enhanced protein expression in mammalian cells using engineered SUMO fusions: secreted phospholipase A2. Protein Sci. 2008 Sep;17(9):1586-95. doi: 10.1110/ps.035576.108. Epub 2008 Jun 6. PMID: 18539905; PMCID: PMC2525526.

[9] Liu L, Spurrier J, Butt TR, Strickler JE. Enhanced protein expression in the baculovirus/insect cell system using engineered SUMO fusions. Protein Expr Purif. 2008 Nov;62(1):21-8. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.07.010. Epub 2008 Aug 5. PMID: 18713650; PMCID: PMC2585507.

[1] Matunis MJ, Coutavas E, Blobel G. A novel ubiquitin-like modification modulates the partitioning of the Ran-GTPase-activating protein RanGAP1 between the cytosol and the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1996 Dec;135(6 Pt 1):1457-70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1457. PMID: 8978815; PMCID: PMC2133973.

[2] Mahajan R, Delphin C, Guan T, Gerace L, Melchior F. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell. 1997 Jan 10;88(1):97-107. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81862-0. PMID: 9019411.

[3] Kim KI, Baek SH, Chung CH. Versatile protein tag, SUMO: its enzymology and biological function. J Cell Physiol. 2002 Jun;191(3):257-68. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10100. PMID: 12012321.

[4] Butt TR, Jonnalagadda S, Monia BP, Sternberg EJ, Marsh JA, Stadel JM, Ecker DJ, Crooke ST. Ubiquitin fusion augments the yield of cloned gene products in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Apr;86(8):2540-4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2540. PMID: 2539593; PMCID: PMC286952.

[5] Ecker DJ, Stadel JM, Butt TR, Marsh JA, Monia BP, Powers DA, Gorman JA, Clark PE, Warren F, Shatzman A, et al. Increasing gene expression in yeast by fusion to ubiquitin. J Biol Chem. 1989 May 5;264(13):7715-9. PMID: 2540202.

[6] Malakhov MP, Mattern MR, Malakhova OA, Drinker M, Weeks SD, Butt TR. SUMO fusions and SUMO-specific protease for efficient expression and purification of proteins. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2004;5(1-2):75-86. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029237.70316.52. PMID: 15263846.

[7] Butt TR, Edavettal SC, Hall JP, Mattern MR. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2005 Sep;43(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016. Epub 2005 Apr 9. PMID: 16084395; PMCID: PMC7129290.

[8] Peroutka RJ, Elshourbagy N, Piech T, Butt TR. Enhanced protein expression in mammalian cells using engineered SUMO fusions: secreted phospholipase A2. Protein Sci. 2008 Sep;17(9):1586-95. doi: 10.1110/ps.035576.108. Epub 2008 Jun 6. PMID: 18539905; PMCID: PMC2525526.

[9] Liu L, Spurrier J, Butt TR, Strickler JE. Enhanced protein expression in the baculovirus/insect cell system using engineered SUMO fusions. Protein Expr Purif. 2008 Nov;62(1):21-8. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.07.010. Epub 2008 Aug 5. PMID: 18713650; PMCID: PMC2585507.